2018: The Disinfo Year in Review

Disinformation was an important feature of the massive protests which gripped the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia in 2018. In most cases, the disinformation narratives that underpinned these events resonated with conspiracy theories analysed in GLOBSEC Trends 2018 Central Europe: One Region, Different Perspectives.

The Czech Republic began the year with a presidential election campaign in which pro-Kremlin disinformation outlets provided direct and indirect support for the incumbent (and eventually re-elected) president Miloš Zeman. The same disinformation outlets also criticised and spread dubious information concerning Zeman’s strongest opponent Jiří Drahoš.

Another important incident which had a profound impact on Central European politics and society was the February murder of Slovak investigation journalist Jan Kuciak and his fiancé Martina Kušnírová. Both were assassinated in their home. In the days that followed, when Slovak authorities were reluctant to provide too much information regarding the police investigation, Czech and Slovak disinformation outlets were quick to fill the gap with explanations including:

- the assassinations and consequent protests followed the Euromaidan script

- Jan’s youthful appearance and murder made him a perfect martyr for George Soros’ group

- the order to kill Kuciak came from the other side of the Atlantic. Slovakia’s entire NGO sector has been infiltrated by the current US administration and George Soros’ people. Jan Kuciak was sacrificed because he did not have a family. His murder was supposed to cause an outbreak of riots and demonstrations against the government[1]

Pro-Kremlin and disinformation outlets in Central Europe also spread disinformation and hoaxes concerning the massive protests in the aftermath of the murders. The peaceful demonstrations, which became a regular occurrence in Slovakia, Czech Republic and cities round the world were depicted as organised by foreign agents - effectively meaning NGOs.

Demonstrators allegedly received financial support from George Soros, a move which indicated the start of Euromaidan revolutions in various countries. The American philanthropist of Hungarian origin is often labelled as the perpetrator and originator of Central Europe’s social unrest and immigration challenges. These are accomplished via Soros’ network of foreign agents – non-governmental and civic organisations that receive funds from the Open Society Foundation. On 28 February, the Czech disinformation outlet Aeronet even published an article claiming that George Soros’ right hand man, Marcello Fabiani, had arrived in Slovakia to witness the protests for himself. No such person exists.[2]

Anti-Soros narratives continue to be disseminated through various channels and by various actors. For example, Atlatszo published research showing that the Hungarian government spent millions on communication and PR for “propaganda campaigns” in 2017. The Hungarian NGO also highlighted that 40.5 million euros were spent on advertising and communicating the results of two ‘national consultations.’ These were propaganda campaigns that flooded the streets of Hungary with posters of George Soros telling people to ‘stop’ him.” From there, the Hungarian government spent over 35.5 million euros on state advertising in the first three months of 2018. This campaign not only targeted Hungarians but also residents of other EU countries. The picture below comes from a Hungarian government-sponsored Facebook post published in Italy.

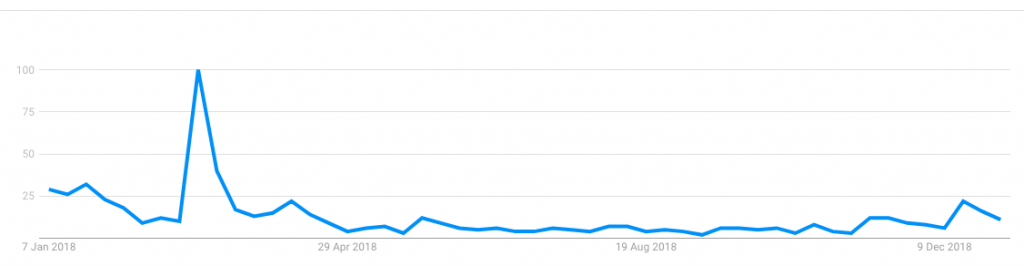

Sustained efforts to discredit George Soros resulted in him becoming one of the most searched for persons within Central Europe, according to Google Search Trends. The following charts demonstrate that ‘’George Soros’’ was the most searched term in the Czech Republic and Slovakia for the week March 4-10 2018.[3] In Hungary the term reached its peak between April 4-10, the week of parliamentary elections which Fidesz won on an anti-immigration platform. Following his party’s victory, the newly elected Hungarian prime minister Victor Orbán held a press conference on April 10 to declare that he had a clear mandate to pass the controversial “Stop Soros” legislative package.[4]

The Czech Republic

Hungary

Slovakia

(Source: Google Trends 2018)

Data from Google Search Trends also reveals that George Soros came fifth on the list of foreigners most searched for by Slovaks in 2018. Other Google statistics show that, on average, 70 Slovaks per month googled information on how to become a professional online troll, 20 per month enquired whether a 9 year-old George Soros served in SS and 20 per month searched for information on how to become a member of the Illuminati.

However, George Soros wasn’t the only issue shaping disinformation throughout Central Europe in 2018. Immigration, the Trump-Putin summit in Helsinki, Kerch Strait incident and the yellow vests were also subject to false and misleading narratives. The region also witnessed changes in how disinformation and the slandering of opponents was spread. For example, there was a significant increase in the use of fake Facebook accounts and trolls, with over 100 employed to support a particular candidate in Slovakia’s local elections. False and copied ‘official’ websites were deployed to launch smear campaigns against opponents.

Increased access to technology has also resulted in the emergence of deep-fake videos. Among the first was a very poor quality video featuring Andrej Kiska. Spread on social media in September, it shows the President of the Slovak Republic being taken into prison and refused bail.

Elsewhere, a 71-year old man was put on trial for terrorist offences in the Czech Republic after cutting down trees and laying them on railway tracks in an attempt to block migration routes. The man, known only as Mr Balda, was a follower of the far-right Czech politician Tomio Okamura who built his career on a strong anti-immigration rhetoric. It is further alleged that the retiree was inspired to cut down the trees by hoaxes regarding the influx of immigrants into the country. His actions, which resulted in two separate train accidents, could result in a 15-year prison sentence.

On a more positive note, 2018 witnessed the rise of Czech and Slovak elves – volunteers that counter online trolls and spread of online disinformation. These are based on the example of the Lithuanian elves, which shared their principles and know-how with their new counterparts. Their emergence also proves that there are individuals who want to actively protect their country from disinformation and foreign subversive efforts and contribute to the resilience of their societies.

Written by Katarína Klingová, GLOBSEC Policy Institute; Lóránt Györi, Political Capital Institute; Jonáš Syrovátka, Prague Security Studies Institute. This brief was published in the framework of project run by the GLOBSEC Policy Institute and supported by the National Endowment for Democracy.

© GLOBSEC Policy Institute

The opinions stated in this report do not necessarily represent the position or views of the GLOBSEC Policy Institute or the National Endowment for Democracy. Responsibility for the information and views expressed therein lies entirely with the authors.

[1] For more information, please see our analytical brief A Sacral Sacrifice, the Assassination of an International Criminal or a Hit from the Other Side of the Atlantic?.

[2] For more information, please see our analytical brief How Far Can They Go? Quantifying the Spread of Disinformation Narratives.

[3] Numbers represent search interest relative to the highest point on the chart for the given region and time. A value of 100 is the peak popularity for the term. A value of 50 means that the term is half as popular. A score of 0 means that there was not enough data for this term.

[4] The ‘Stop Soros’ package of bills passed by the Hungarian government in June 2018 criminalises some help given to illegal immigrants and thus narrows the work of NGOs working in this field, making their workers liable for jail terms for helping migrants to seek asylum when they are not entitled to it.