CEE Activities of the Muslim Brotherhood: Czech Republic, Poland, Serbia

GLOBSEC’s partnership with the Counter Extremism Project has produced a second report in the project CEE Activities of the Muslim Brotherhood. This publication presents three case studies from the region, the Czech Republic, Poland and Serbia. The findings below are the result of conducted interviews with four groups of individuals — experts from academia, government officials, members of Muslim communities, and voices in opposition to the studied groups. In addition to the interviews, the research team used primary sources such as the groups’ official websites, publications, press releases, letters, and other material they published. The team also relied on secondary sources, including academic literature, news articles, and other websites.

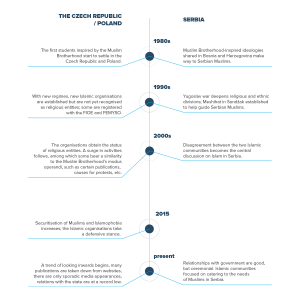

The three countries have seen dynamic developments of their various Islamic communities, be it autochthonous, expatriate or convert communities. The timeline below briefly summarises the largest trends observed in this research.

Key Findings:

- The studied organisations had been reaching out in their early development to the Federation of Islamic Organisations in Europe (FIOE) and the Forum of European Muslim Youth and Student Organisations (FEMYSO). In the case of Serbia, there might be a possible Muslim Brotherhood tie facilitated via Bosnia and Herzegovina. However, formal connections to the Muslim Brotherhood-run organisations currently appear to be inoperative.

- There has been a development in Serbia that points at intracommunal proselytisation. This effort is, however, not tied to the ideology of the Muslim Brotherhood but to the more assertive and even more extremist Takfiris. Also relevant might be online posts of images of successful conversions disseminated by one organisation based in the Czech Republic, although the origin of these images is dubious. Overall, there has not been any detected da’wa activity noted towards non-Muslims and all publication activities have decreased dramatically.

- The studied groups surely try to advocate for Muslims and to a certain degree compete to represent this minority in their respective countries. However, since the so called “refugee crisis” of 2015, the relationships with government institutions in the Czech Republic and Poland have been gloomy. In Serbia, while the relationship with the government is perceived as good, it appears to be largely of a ceremonial character and does not offer any meaningful practical advantages for the groups studied for this report.

- Given the effects of the recent terrorist attacks in Europe as well as the “refugee crisis” the communities in all three countries aim to improve the position and perception of Muslims, and further advance their financial backings to continue with the operation of their mosques and centres.

- According to one expert interviewed on the situation in the Czech Republic, one trace of Muslim Brotherhood influence was visible during the Egyptian Revolution. At that time Muslims from Prague and Brno were among members of the Brotherhood. However, this was not a well-functioning group, as an internal split occurred since some were supporting the then Minister of Defence Abdel Fattah el-Sisi and others joined the protests against el-Sisi after the military coup. Currently, in the Czech Republic, these individuals have no time or energy, “suffering from cabin fever” because there are simply too few of them and the movement was not going anywhere.