How to Make Geneva a (First) Success Story

Taking into account Iran’s geopolitical approach to the Yemen conflict

By prof. PhDr. Peter Terem, PhD

Following a conflict that has raged for nearly 4 years, Yemen’s warring parties will sit down at peace talks this week, in an effort to bring an end to the bloodshed. These peace talks must be aimed at building a foundation for stability if Yemen is to have any hope for a more peaceful, prosperous future. The conflict is at a tipping point as the primary sticking point will be the western port city of Hudaydah which was seized by the Iranian-backed Houthi movement and is currently surrounded by the Saudi-led coalition forces under the leadership of the United Arab Emirates. It seems that the geopolitical aspect through the involvement of regional players presents major implications for conflict resolution. Therefore, in order to find a sustainable solution, it is important to take into account the geopolitical motives in play. This article aims to explore Iran’s geopolitical approach to the Yemeni conflict and provides four resulting recommendations that might create a foundation for trust-building by achieving small diplomatic victories for all parties.

GLOBSEC recommends the following objectives for the Geneva talks:

- First, to agree on humanitarian relief for the Yemeni population by handing over control of Hudaydah to improve the flow of humanitarian aid.

- Second, to push all stakeholders to abide to the previous agreed UN resolutions, in particular to cease all weapons imports from other countries and to end the recruiting of child soldiers and use of landmines

- Third, to strengthen joint commitments to rid Yemen of terrorism and extremism, particularly in the forms of AQAP and Daesh. With all parties striving to defeat terrorism, a common enemy, all need to agree on terms to limit the room for terrorism and to establish a strong society resilient to radicalisation.

- Fourth, Tehran’s ‘Yemen Card’ should be included in the wider regional talks. If Iran wants to defuse the current situation and rely on the other signatories’ goodwill to uphold the nuclear deal it needs to stop its aggressive expansionism in the region.

How it all began

After years of mounting instability, Yemen, even before the conflict the poorest country in the Middle East, is reduced to rubble. According to United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres the country currently hosts the largest humanitarian challenge the world has witnessed in recent years.[i] Despite the influx of foreign aid, a major crisis remains. The failed political transition in the aftermath of the region-wide Arab Spring uprisings spiralled into a devastating civil war that soon became internationalised to a large extent. Initially, the conflict organically spilled over the borders through cross-border conflict, illicit trade and a migration wave, but soon became an arena of strategic rivalry between regional powers.

In another attempt to resume the long-stalled peace process, UN special envoy for Yemen Martin Griffiths has been busy over the past few months, mediating between the Gulf-backed government and the Houthi rebels supported by Iran. These efforts will culminate in talks in Geneva this week. Yemen’s fractious political landscape makes conflict resolution difficult to achieve. The complex dynamism between the power institutions of the modern nation-state and traditional societal hierarchies leads to scattered alliances across institutions, families and tribes. Even before the contemporary conflict, these rivalling structures have been the cause of decades of power struggles. Since the unification of North Yemen and South Yemen in 1990, multiple secessionists movements and complex alliances have sprung up in both regions. As religious denominations are geographically easily delineated, the conflict increasingly became entrenched among the Zadi-Shia in the north and the Shafi-Sunnis that dominate the region formerly known as South Yemen, effectively bringing sectarianism to the forefront.[ii] Additionally, and especially in the aftermath of the defeat in Syria and Iraq, terrorism has fed fuel to the fire as Daesh and AQAP rival for the spot of most merciless organisation.[iii]

It is in this volatile situation of factional rivalries that Iran takes advantage by interfering in a conflict at its biggest rival’s southern border. As a continuation of its recently increased regional activism in the Middle East, including but not limited to Syria, Lebanon and Bahrain, Tehran political and military meddling brought the Yemeni conflict onto the regional chess board with its citizens being reduced to ordinary pawns. After three years of conflict, with no resolution in the offing, it is necessary to approach the conflict from a regional perspective. Only by taking into account the motives of all relevant stakeholders a better understanding of the conflict might be achieved, and a political agreement in Geneva reached.

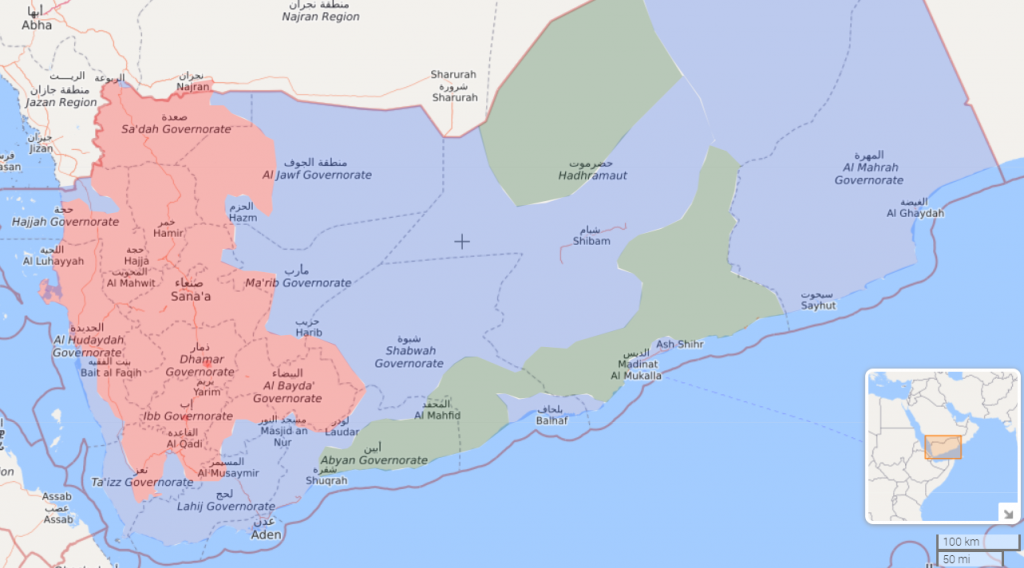

Conflict map of the current situation in Yemen. Red shows the Houthi territory, whilst blue and green show the Yemeni forces and terrorist movements respectively. (Source: Liveuamap.com, April 28, 2018).

Geopolitics

One cause of confusion is that the conflict is often referred to as a civil war, which indirectly implies solely internal affairs lay at the foundation. Indeed, rarely national borders contain conflicts. Stress on neighbouring countries occurs through the triggered migration wave - according to the UN 190,352 have fled the country in search of safety - and a surge of cross-border crime through smuggling of both people and goods leads to a spill over to Saudi Arabia and Oman, as well as Eastern African countries across the Gulf of Aden.[iv]

Yet, in addition to the abovementioned organic spill over, the conflict in Yemen has bigger regional repercussions reaching as far as the Elburz Mountains. Tehran’s involvement in the conflict demonstrates that more is at stake. The Gulf States have raised concerns about its growing influence in the region and especially regarding the more aggressive stance of the Revolutionary Guards’ Al-Quds force in foreign conflicts. It is obvious that the role Iran plays in the conflict cannot be discounted either, posing an existential threat to those states lying on the Yemeni border.

Tehran’s foot between the door

To answer the question how the Iranians got their foot between the door, it is necessary to look back to the history of Yemen before it was even unified. Iran has always maintained good relations with the Zaydi community in northern Yemen.[vi] The immediate release of Iranian prisoners and the opening of direct flights to Tehran after the Houthi’s takeover of Sanaa demonstrate this relationship.[vii] The Houthi movement, formally known as the Ansar Allah (The Supporters of God), is the political representation of the Shia-Zaydi community in the mountainous provinces bordering Saudi Arabia that has strived since the early nineties for more autonomy in the absence of strong central authority. Although the first president of the new republic Ali Abdullah Saleh, who had been ruling North Yemen since 1978, initially alienated the southern tribes by favouring the northern capital region around Sanaa, the Houthis also chafed when their homeland became impoverished over time.[viii] The movement ramped up its violent rebellion in 2004, developing into a full-scale civil war over the years and gaining momentum after the 2011 uprising in the wake of the Arab Spring forcing Saleh to step down after demonstrations lasted.[ix]

Although his rule has been characterised by wide-spread nepotism and corruption - Yemen ranked 164 out of 182 in the 2011 Corruption Perceptions Index and the UN estimated that during his reign the president and his inner circle have amassed up to $60 billion– in a surprising move the forces loyal to him forged a united front with the Houthis against his former deputy and successor Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi.[x] This despite the latter being elected in 2012 to head a two-year term transitional government after intense brokering by the Gulf States, especially Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, in an attempt to prevent a further escalation of violence.[xi]

In order to avoid sparking any sectarian tensions, there have never been any official records on Yemen’s individual religious identities, but the US Department of State estimates that 65% of Yemenis follow the Sunni-Shafi school of thought, while followers of the Shia-Zaydi school account for an estimated 35% of the population.[xii] The geographical spread of both denominations is fairly similar to the former two states, with the Sunni population situated in the Southern governates and Shias concentrated in the North-West. Although there have been numerous examples of low-level conflicts between the country’s different religious denominations, sectarian violence had always been relatively low. A notorious example is the Salafi Dar al-Hadith religious school, which has been a source of conflict between Houthis and Salafis in Dama. Moreover, the resurgence of Shia celebrations occasionally led to clashes in the pre-war years, especially in Sanaa.[xiii] Nonetheless, it seems that the religion-politics nexus in Yemen gradually became more apparent as a result of developing power politics. Yet, the adaptation of such increasingly sectarian discourse cannot be solely explained as opportunism by local actors. It must also be seen in light of the bigger sectarian division that splits the region between Islam’s main denominations. The advantages of the Houthis towards historically-dominated Shafi areas such as Ma’ri, Al Bayda, Radaa or Taiz have fed fuel to the sectarian fire. Not only Daesh and Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) have taken advantage of such sensitivity by having successfully recruited traditional tribesmen to join forces, also for Tehran this latent segmentation proved to be useful for expanding its influence into the South Arabian Peninsula.[xiv] The instrumentalisation of sectarianist differences has proven to be effective for popular mobilisations in Hezbollah’s Lebanon, Assad’s Syria and on the streets of Bahrain.[xv] It seems that also in Yemen Tehran manages to play the Shia card very well to find its way in a country where it initially didn’t enjoy a strong power base.

Iran’s bigger chess game

The implosion of the Hadi government led to an internal power struggle that resulted in significant challenges to regional security. As stated above, it would be inadequate to define the situation as a civil war, as it is simultaneously being fought on three fronts: internal, regional and the international war against terrorism. This three-front war between the government and its backers, the Houthis and Daesh/AQAP is not primarily about the insurgency, nor the Yemen people: it is primarily about geopolitics. The struggle for regional supremacy between US-backed Saudi Arabia and its Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) allies on one side and the Islamic Republic of Iran, with implicit backing from Russia on the other, reeks of the nineteenth century when values had no place in the pursuit of interest. Therefore, in March 2015, the GCC saw no other option than to act as Houthi rebels violently ousted President Hadi’s recognised government, prompting an international Saudi-led coalition comprising nine other countries into an armed intervention. In an attempt to limit Tehran’s growing influence, Operation ‘Decisive Storm’ successfully halted the Houthi rapid movement, and thus avoided the emergence of an Iranian stronghold.

To complicate the situation on the ground even more, the coalition had to fight on multiple fronts as it simultaneously fenced off a growing terrorist threat. While the Saudis mainly focused on the fight in northern Yemen, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the only GCC country with experience in the field, actively led counter-terror operations. In line with its strategy to focus on local movements, Al-Qaeda’s fiercest branch AQAP reinvented itself as Ansar al-Sharia in an attempt to win the support of southern tribes, particularly those along the southern coast like Zinjibar and Ja’ar. The fact that AQAP centralised earlier looser terrorist structures in the region makes the group also locally entrenched in neighbouring countries dragging in the international community into the conflict.[xvi] In recent months, however, a significant force of local fighters under Abu Dhabi’s military leadership with the support of US drone campaigns has successfully reclaimed much of former terrorist territory.[xvii] AQAP is now a shadow of its former might, when it was capable of carrying out devastating attacks such as the Charlie Hebdo massacre in 2015. The reduction in its financial, logistical and organisational power in its Yemen HQ since this time has been a major contributor to AQAP’s diminishing threat. Additionally, aid has been able to more easily reach areas liberated from AQAP, with the UAE dedicating a large portion of its $3.8bn Yemen aid contribution to rebuilding affected areas.[xviii] Nevertheless, the threat still remains with Daesh seeking to gain influence in war-torn southwest Yemen.

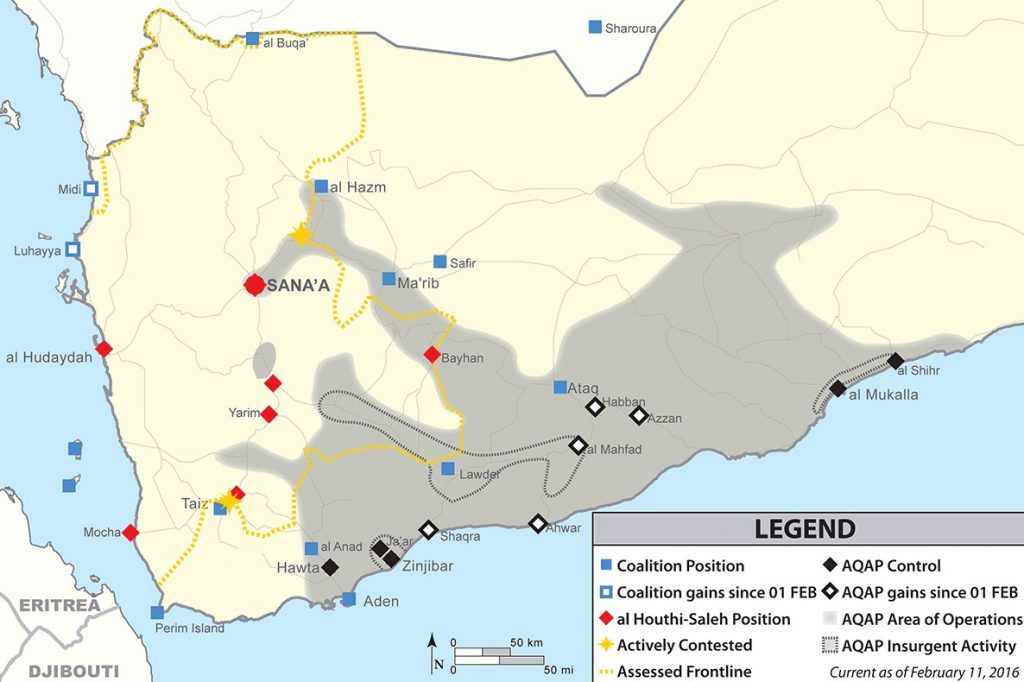

Conflict map of the terrorist presence in Yemen on February 1, 2016. Before the UAE initiated its counterterrorism operations, AQAP area of operations stretched along the whole southern coast of Yemen. Two years later, AQAP territory has been almost completely reconquered, with only a few hundred fighters left. (Source: James Towey, criticalthreats.org, February 17, 2016).

Qiam missiles and ideological copy-paste

It is debatable to what extent Iran directly controls the Houthis, but it is undeniable that without their backing their military campaign would have little chance of success.[xix] As early as 2012, there were recurring reports concerning alleged arm shipments to Yemen coordinated by the Quds Force. Multiple navies, including France and Australia, have intercepted deliveries bound for the Houthi-held territory south the strategic port of Hudaydah.[xx] Even after the adaptation of an embargo by UN Security Council resolution 2216, it was demonstrated on multiple occasions that the Houthis continued to have access to Iranian-produced Qiam ballistic missiles, heavy arms and even drones enabling them to reach targets far beyond national borders. After all, it was Iranian technology that hit Riyadh’s King Khaled International Airport in July and November 2017.[xxi] Since 2017, there has been a significant increase in the number of Qiam rocket attacks into Saudi Arabia and the UAE, with the latter experiencing multiple attacks recent months .[xxii] There has also been an increase in attacks on shipping in the Bab el Mandeb, attacking Aramco oil tankers, opening a second indirect Iranian front against the Saudis and wider coalition. Removing control of the port of Hudaydah from the Houthi rebels would cut of a major lifeline for smuggled Iranian weapons.

Additionally, multiple reports have indicated the active involvement of the Revolutionary Guards and Hezbollah forces by providing military training and technical assistance, a strategy remarkably similar to the one applied during the first years of the Syrian war, which indicates the existence of a bigger military strategy for the region.[xxiii] Although its war costs are marginal compared with the Saudi-led coalition, Iran’s population, facing soaring inflation rates, a collapse of the currency and a fragile economy due to reimposed US sanctions, has taken to the streets of Tehran on multiple occasions to express its frustrations about spending in foreign conflicts.[xxiv]

The aggressive meddling is not limited to purely military means. Teheran’s ideology has progressively found its way into the Houthi’s dogma, especially after their leader Bader al-Houthi’s visit to Iran’s religious stronghold of Qom.[xxv] The religious character of the group is further underlined by its increasing focus on the conspiracy theory that Israel and the United States are taking over the region, and by adopting similar terminology. Not to mention their chilling slogan “Allahu Akbar, death to the US, death to Israel, curse the Jews and victory for Islam” which became the movement’s trademark in the early 2000s. Although societal division across sectarian lines seemed to be a useful instrument to put a foot between the door, it would be unfair to label Iran’s motives solely as religious-ideological.[xxvi] After all, the Zaydi denomination is inherently different to Twelver Shiism, which is widespread in the Levant. Thus, the question remains: what are the primary drivers of Tehran’s interest in Yemen?

The importance of Yemen

Iran’s political motives in Yemen are three-fold. First, Tehran has used turmoil here to successfully shift attention away from the bloody conflict in Syria, where Bashar al-Assad’s reign would have finished a long time ago if it wasn’t for the direct support of both Iran and Russia. As Western-backed forces began to lose ground, the GCC watched idly as terrorist groups filled the emerging power vacuum only to be replaced by Hezbollah fighters, Iranian-backed militias and Assad loyalists who did not shy away from slaughtering civilians with chemical weapons and indiscriminate aerial bombardments.

Today, there is no doubt that Iran is on the winning side in Syria. It has successfully maintained and even expanded its influence over the Levant region, including Lebanon and Iraq. This increased room for manoeuvre is partly because GCC states were too occupied protecting their security interests from a war in their backyard. With the Syrian conflict seemingly about to enter its final stage in favour of Assad it is likely the struggle for the Middle East will shift, placing Yemen on the frontline of a new geopolitical struggle, much to the chagrin of Israel.[xxvii] If Iran also prevails in Yemen, it will be stronger than ever in the region.

The second motive concerns the Bab el Mandeb. Tehran’s interests here are purely strategic given that Yemen’s natural resources offer limited to no added value to oil-rich Iran. Nor does the conflict directly endangers any of the country’s economic interests. On the contrary, the Bab el Mandeb is the gateway to the Red Sea, and thus a vital trading link between Europe and the GCC. According to recent data by the Energy Information Administration (EIA), 4.8 million barrels of petroleum and crude oil products pass along the Yemen coast on a daily basis.[xxviii] Bearing in mind that avoiding the narrow strait would increase shipping times by 28%, it soon becomes clear what worrying signs Iran sends out by gaining a foothold in Yemen. Not only does it create the perception of having capabilities to strike the Saudi mainland, it also suggests that uninterrupted international oil trade relies on its goodwill. Recent attacks on oil tankers prompted Riyadh to temporarily avoid this emerging chokepoint.[xxix] Lastly, controlling the Bab also means that Iran can expand its sphere of influence by creating a naval Shia axis from the Persian Gulf via the Southern Arabian Peninsula to Sinai, providing a supply routes to Hamas in the process. In other words, if Iran succeeds the whole region faces a geopolitical repositioning.

Third, the Yemen conflict provides Tehran with an important bargaining chip in broader Middle Eastern negotiations - the so-called ‘Yemen card’. As the Houthi alliance seems to strive for power transition through the barrel of a gun rather than 21st century diplomacy, multiple UN negotiations have already stalled. In the broader game currently being played in the Middle East, Yemen is a valuable pawn that gives Tehran leverage in future talks, including those coming up in Geneva next month.

How to make Geneva a (first) success story

Given the complex nature of the conflict, a breakthrough on September 6 by UN Special Envoy Griffiths seems far away, especially after the publication of the UN’s latest report was criticized by multiple Gulf countries as being disproportionally one-sided.[xxx] To achieve a sustainable resolution, it is important that mutual trust between the GCC-backed Yemen government and Iranian-backed Houthi rebels is established. Since 2012, the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) has labelled the situation in Yemen as a humanitarian crisis, which has “resulted in a complex emergency that includes widespread conflict-driven displacement and a slow-onset crisis in food security, malnutrition and outbreak of communicable diseases, particularly waterborne diseases”.[xxxi] In a country where almost half the population are under 15, diseases such as Cholera and Diphtheria cause many young victims. Environmental disasters like the 2015 Chapala and Megh cyclones, the 2016 floods and structural water scarcity contribute to further human suffering in addition to direct conflict-related hardship.[xxxii]

With its infrastructure in ruins and young deprived of an education, the first step towards trust-building might be an agreement on humanitarian relief for Yemen’s population. Tackling common concerns first has proven to be effective in peace talks before. This trust can only be based on ensuring the port of Hudaydah, responsible for 70% of Yemen’s humanitarian imports, operates more efficiently and effectively.[xxxiii] However, the diversion of shipments to the conflict zone, delays in delivering cholera vaccinations and extortionate taxes on imports demonstrate that this cannot be achieved under the control of the Houthis, who refuse to negotiate the release of the port. Peace talks should, therefore, include a deadline to relinquish control of the port and hand over authority to the United Nations.

A second recommendation would be to ensure all sides abide by previous UN resolutions, particularly the arms embargo. Additionally, all parties must end the recruitment of child soldiers and use of landmines in accordance with UN resolution 1261. International agencies under the flag of the UN should control should also uphold their commitment to objective monitoring. Thirdly, the warring parties should acknowledge that they have a common enemy that did not receive an invitation to the negotiating table: terrorists. Both sides aspire to a safe country that upholds human rights. Together, all can agree on terms to limit the room for terrorism and establish a strong society that’s resilient to radicalisation.

Finally, the long-term build-up of multiple events over the past years limit the regional powers to path-dependency politics, making it difficult to make a U-turn in policy. Therefore, the international community needs to use the disruptive force of the unexpected snapback of US sanctions against Iran. Tehran needs to understand that if it wants to defuse the current situation and rely on the other signatories’ goodwill to uphold the nuclear deal it must stop its aggressive expansionism in the region. In other words, if it doesn’t want to be isolated even further, Iran must give up its ‘Yemen card’. If mutual trust can be built during next month’s talks, all stakeholders can start peace negotiations scheduled for later this year in good faith. In the end, a sustainable agreement for the Yemen conflict is one where both sides can claim a diplomatic victory.

Peter Terem is a Professor and Head of Department of International Relations and Diplomacy, Faculty of Political Science and International Relations, Matej Bel University, Banská Bystrica

Sources

[i] Forbes (April 5, 2018): “Yemen Became the World’s Worst Humanitarian Crisis.” Accessed on September 3, 2018 on https://www.forbes.com/sites/ewelinaochab/2018/04/05/yemen-became-the-worlds-worst-humanitarian-crisis/#325c769b5050.

[ii] Emad Y. Kaddorah. “The regional geo-sectarian contest over the gulf.” Insight Turkey 20, no. 2 (2018): 21-32.

[iii] United Nations Security Council (January 31, 2017): “Letter dated 27 January 2017 from the Panel of Experts on Yemen addressed to the President of the Security Council.“ Accessed on August 28, 2018 on https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_2017_81.pdf.

[iv] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (February 9, 2018): “Yemen Emergency.” Accessed on August 30, 2018 on http://www.unhcr.org/yemen-emergency.html.

[v] Tisdall, Simon (March 26, 2015): “Iran-Saudi Proxy War in Yemen Explodes into Region-Wide Crisis.” Accessed August 27, 2018 on http://www.alternet.org/iran-saudi-proxy-war-yemen -explodes-region-wide-crisis.

[vi] Terril, Andrew. “The Saudi-Iranian rivalry and the future of the Middle East Security.” Current Politics and Economics of the Middle East 3, no. 4 (2011): 513-557.

[vii] Reuters (March 27, 2015): “Elite Iranian guards training Yemen’s Houthis: U.S. Officials.” Accessed on August 29, 2018 on https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security-houthis-iran/elite-iranian-guards-training-yemens-houthis-u-s-officials-idUSKBN0MN2MI20150327. Qatar Tribune (March 2, 2015): “First Irani flight lands in Shiite-held Yemen Capital”. Accessed on August 29, 2018 on http://archive.qatar-tribune.com/viewnews.aspx?n=202A449E-C5B0-47DB-B990-949DF15573D6&d=2015030.

[viii] Reuters (June 15, 2018): “Why Yemen is at war.” Accessed on August 26, 2018 on https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security-explainer/why-yemen-is-at-war-idUSKBN1JB1TE.

[ix] Neriah, Jacques. “Yemen changes hands. Will an Iranian Stronghold emerge near the entrance to the read sea?” Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs 14, no. 32 (2014).

[x] Transparency International (2011): “The Corruption Perceptions Index 2011.” Accessed on August 30, 2018 on https://www.transparency.org/cpi2011/results. United Nations Security Council (February 20, 2015): “Letter dated 20 February 2015 from the Panel of Experts on Yemen established pursuant to Security Council Resolution 2140 (2014) addressed to the President of the Security Council.“ Accessed on August 28, 2018 on https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_2015_125.pdf.

[xi] Juneau, Thomas. “Iran’s policy towards the Houthis in Yemen: a limited return on a modest investment.” International Affairs 92, no. 3 (2016): 647-663.

[xii] United States Department of State Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (2012): “International Religious Freedom Report for 2012” Accessed on August 23, 2018 on https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/208632.pdf.

[xiii] Ibid.

[xiv] United Nations Security Council (February 20, 2015): “Letter dated 20 February 2015 from the Panel of Experts on Yemen established pursuant to Security Council resolution 2140 (2014) addressed to the President of the Security Council.“ Accessed on August 27, 2018 on https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/un-documents/yemen/.

[xv] Spyer, Jonathan. “Patterns of subversion: Iranian use of proxies in the Middle East.” Middle East Review of International Affairs 20, no. 2 (2016): 29-36.

[xvi] United Nations Security Council (February 20, 2015): “Letter dated 20 February 2015 from the Panel of Experts on Yemen established pursuant to Security Council resolution 2140 (2014) addressed to the President of the Security Council.“ Accessed on August 27, 2018 on https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/un-documents/yemen/.

[xvii] The Independent (August 15, 2018): “Inside the UAE’s war on al-Qaeda in Yemen.” Accessed on August 29, 2018 on https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/uae-yemen-civil-war-al-qaeda-aden-dar-saad-gulf-saudi-arabia-conflict-a8492021.html.

[xviii] Reliefweb (May 16, 2018): “UAE assistance to Yemen totals AED13.82 billion.” Accessed on September 3, 2018 on https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/uae-assistance-yemen-totals-aed1382-billion.

[xix] Reuters (April 30, 2018): “Commentary: To contain Iran, look first to Yemen – not sanctions.” Accessed on August 28, 2018 on https://www.reuters.com/article/us-pascual-yemen-commentary/commentary-to-contain-iran-look-first-to-yemen-not-sanctions-idUSKBN1I11JP.

[xx] United Nations Security Council (February 20, 2015): “Letter dated 20 February 2015 from the Panel of Experts on Yemen established pursuant to Security Council resolution 2140 (2014) addressed to the President of the Security Council.“ Accessed on August 27, 2018 on https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/un-documents/yemen/.

[xxi] CNN (December 15, 2017): “Haley: Missile debris ‘proof’ of Iran’s UN violations.” (2017). Accessed on August 29, 2018 on https://edition.cnn.com/2017/12/14/politics/haley-us-evidence-iran-yemen-rebels/index.html.

[xxii] The Independent (August 28, 2018): “UAE denies Houthi rebels attacked Dubai airport with armed drone.” Accessed on August 29, 2018 on https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/uae-dubai-airport-drone-attack-houthi-rebels-yemen-emirates-a8510551.html.

[xxiii] Reuters (March 21, 2017): “Exclusive: Iran steps up support for Houthis in Yemen’s war.” Accessed on August 30, 2018 on https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-iran-houthis/exclusive-iran-steps-up-support-for-houthis-in-yemens-war-sources-idUSKBN16S22R.

[xxiv] Brookings Institute (December 6, 2016): “In Yemen, Iran outsmarts Saudi Arabia again.” Accessed on August 27, 2018 on https://www.brookings.edu/blog/markaz/2017/12/06/in-yemen-iran-outsmarts-saudi-arabia-again. Foreign Affairs (January 5, 2018): “Why the protests won’t change Iran’s foreign policy”. Accessed on August 30, 2018 on https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/iran/2018-01-05/why-protests-wont-change-irans-foreign-policy. Foreign Policy (August 6, 2018): “U.S. turns up heat on Iran’s economy, adding fuel to massive protests.” Accessed on August 30, 2018 on https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/08/06/u-s-turns-up-heat-on-irans-economy-adding-fuel-to-massive-protests-sanctions-jcpoa/. Wall Street Journal (January 2, 2018): “Iran’s spending on foreign conflicts raises protesters’ ire.” Accessed on August 30, 2018 on https://www.wsj.com/articles/irans-spending-on-foreign-proxies-raises-protesters-ire-1514920398.

[xxv] Juneau, Thomas. “Iran’s policy towards the Houthis in Yemen: a limited return on a modest investment.” International Affairs 92, no. 3 (2016): 647-663.

[xxvi] Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Centre (October 1, 2015): “War in Yemen: the view from Iran.” Accessed on August 30, 2018 on https://www.cmi.no/publications/5654-war-in-yemen-the-view-from-iran.

[xxvii] Haaretz (August 31, 2018): “Iran deploys missiles in Iraq capable of reaching Israel.” Accessed on August 31, 2018 on https://www.haaretz.com/middle-east-news/iran/iran-placing-missiles-in-iraq-in-message-to-u-s-israel-sources-say-1.6433629.

[xxviii] Energy Information Administration (August 4, 2017): “Three important oil chokepoints are located around the Arabian Peninsula.“ Accessed on August 30, 2018 on https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=32352.

[xxix] Bloomberg (July 26, 2018): “Bab el-Mandeb, an Emerging Chokepoint for Middle East Oil Flows.” Accessed on August 30, 2018 on https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-07-26/bab-el-mandeb-an-emerging-chokepoint-for-middle-east-oil-flows.

[xxx] BBC (August 29, 2018): “Yemen conflict: Coalition rejects UN human rights report.” Accessed on August 30, 2018 on https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-45348364.

[xxxi] International Organization for Migration (2018): “Yemen. Migration Crisis Operational Framework (MCOF) 2017-2018.“ Accessed on August 28, 2018 on https://www.iom.int/sites/default/files/our_work/DOE/MCOF/MCOF-Yemen-2017-2018.pdf.

[xxxii] Ibid.

[xxxiii] Human Rights Watch (June 26, 2018): “Yemen: minimize harm to civilians in Hodeidah.” Accessed on August 29, 2018 on https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/06/26/yemen-minimize-harm-civilians-hodeidah.